‘Twins’

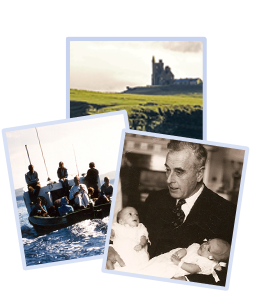

The heart of a human foetus starts to beat three weeks after conception. Mine started beating in the middle of March 1964. A few millimeters away another heart was beating alongside mine. It belonged to my identical twin. Our hearts beat in loose synchronicity over seven hundred million times until he was killed, aged fourteen.

His names were Nicholas Timothy Knatchbull and he was born at 3:40 on a cloudy Wednesday afternoon in November at King’s College Hospital in Camberwell, London. Twenty minutes later, I was born, to be named Timothy Nicholas Knatchbull.

In simple terms, identical twins are produced when a fertilised egg splits and develops into two embryos. Essentially one human divides at an early stage and emerges from the womb as two genetically identical clones. It is not just that they look the same; to all intents and purposes, they are the same. Even DNA analysis will not reliably tell them apart. It has therefore always surprised me that Nick was half a pound heavier than me and remained so for the rest of his life. We never paid any attention to diet and rarely looked at the bathroom scales but whenever we did, there were always eight ounces more of him than me. For such apparently identical children, it was equally surprising that we had feet of different sizes. More precisely, we had three feet one size, while my left foot was half a size bigger. This frustrated my mother whenever it came to buying shoes.

‘Bomb’

On the cliff top about two hundred yards away, the Gardai had parked close to a caravan opposite our lobster pots. They were looking down on the boat as it approached the shore at a slight angle, closing in on the buoys and still moving. As my grandfather slowed the boat, my grandmother turned to my mother and said, ‘Isn’t this a beautiful day?’ We were now as far from the harbour as we were going that day. My father’s account reads:

‘Just before we reached the place where the lobster pots [were], I moved from the [fishing] seat and sat down on the bench running along the starboard between my mother and Dickie and facing the engine. Just as I saw the first buoy Dickie speeded up the engine and I turned round so that my legs were still left on the inside of the boat, and my body was looking out over the starboard side trying to spot the buoy.

On the roof, my head was turned in the direction of the buoys off to my right. My bottom was tucked inside the old tyre. My body was facing the bow of the boat; my arms were tucked up around my knees in front of me’.

William Wilkinson again:

‘As the boat approached us I had lost a wee bit of interest in the fishing as I wanted to focus my eyes on this man, for nosiness shall we say, because I had never seen him before. As the boat got closer I was given a nice clear view of him because he wasn’t much further than maybe about thirty yards. The boat passed and I said, ‘This boat is moving towards the shore or rocks.’ Charlie replied, ‘He is probably going over to lift lobster pots.’ When it was about sixty yards away, I still had it under observation when all of a sudden there was just this ‘boom’.’

According to Garda Mullins, at 11:46, ‘Suddenly I heard an enormous bang. I saw the boat go up in pieces in the air. There was a lot of smoke and in a second the boat had disappeared. All I could see were very small pieces of wood floating on the water.’

My father later wrote:

‘My first memory is of a crack, rather than a bang, and then I regained consciousness under the water, being swirled round and round and head over heels. I did not stop to wonder what had happened. I just knew an absolute disaster had occurred. I tried to fight myself up to the surface and eventually reached a piece of wood which I put my arms around and this was also being tossed around by the force of the explosion in the water.’

My mother wrote in her diary:

‘I only remember terrific explosion (and thinking it was the engine which had been playing up) and immediately being submerged and going down and down in sea with water rushing in ears. Frightened I would not get up before drowning (forgot it was shallow) or get caught beneath hull. Remembered Darling Daddy’s story of HMS Kelly sinking. Put my hands over nose and mouth to stop swallowing water and made a note to tell him I had if I got up. Remembered Dodo could swim but worried she would get bad chill. It finally got lighter and I surfaced hitting a piece of wood and not minding facial injuries I later thought caused by it! Mentally relieved to hear Darling John’s agonised voice shouting ‘Help my wife’ or ‘Where’s my wife?’ quite close. Vaguely aware of other voices before mercifully losing consciousness.’

My grandfather was at the helm three or four feet behind me and slightly to my right. The gelignite under the deck must have been between us because as we rose into the air we went in different directions. I remember a sensation, as if I had been hit with a club, and a tearing sound. I do not remember my journey through the air or hitting the water but before the debris finished raining down, I was unconscious and about a hundred feet from my grandfather.

Eighty-six miles away in Granard, the Gardai had no idea what had just happened outside Mullaghmore but they were convinced they had stopped two IRA men involved in a serious crime and they now decided to act. Within five minutes of the explosion Garda James Lohan stepped up to Thomas McMahon and said, ‘I am arresting you under section thirty of the Offences against the State Act 1939. You are not obliged to say anything unless you wish to do so but anything you say will be taken down in writing and may be given in evidence.’ McMahon made no reaction. Next Lohan went to the man who had been driving him. The Gardai were soon to find out that his real name was Francis McGirl. As Lohan used the same words, his right hand on the prisoner’s shoulder, McGirl sat and grinned.

‘The Sound of the Bomb’

1

At twilight one afternoon, I twisted Philip’s arm and he agreed to come out with me so I could drive the Land-Rover. I mistimed the use of the clutch when changing up a gear, and as I did so I suddenly had an extraordinary sensation. It was as if a very loud bang had occurred. I thought maybe I had damaged the engine or the gearbox, but when I looked at Philip I saw no reaction. I said nothing. That night in bed I thought about driving the Land-Rover again. Suddenly a bang filled my head. I was surprised, slightly scared at first, and completely perplexed. Again and again in the coming months the sound returned to me. I had no idea why.

In July 1980 my parents took us on a family holiday to the South of France. I was playing golf with my brother Joe at the Mandelieu Golf Club near Cannes. We had to cross a small river in a boat and walk to the next hole, passing under a railway bridge. As I did so a fast-moving train passed overhead. The suddenness of it took me completely by surprise, terrifying me. As suddenly as the noise arrived, it disappeared and I realized I was screaming in fear. I walked on shaking like a leaf, and as soon as I could I made a big joke out of it with Joe and left it at that.

I started to think more and more about what was going on in my head. Why had the sound of this train unnerved me so much? The episode persuaded me that the sound of the bomb was somehow travelling around with me every day, suppressed in my mind but waiting to pop up when a stimulus came along. It was almost impossible for me to predict when I would hear it but I began to notice patterns, and the more I noticed the patterns, the more familiar I felt with my own psyche. I had many almost invisible scars from the bomb, and this mental scar seemed of little more significance than the scar on my left thumb. Just as I might roll a pebble around in my pocket, I sometimes found myself in moments of solitude, reflection or just boredom, looking down and touching the familiar old scar. It is like the wrapper off a childhood toy found in the back of a cupboard; the toy and childhood have long since gone but the memories are summoned.

I began to settle in with this mental scar. I knew that I could not predict or control it. I knew that no one else could tell when I was experiencing it. Strangely, as well as being eerie, I found it almost reassuring. I was so lacking in symptoms, and so often complimented for being so ‘strong’ that I sometimes wondered if I had a screw loose and had turned into a psychopath. Nicky was dead and I had not had any sort of breakdown. The sound in my head proved I was feeling something. It was intriguing, perhaps satisfying; in a macabre way, sometimes it almost entertained me. When would it go off next?

2

… in moments of quietness I found myself thinking again of what it must have been like for my parents when Nick had been killed. I realised that many questions about Nick’s death still hung unanswered at the back of my mind, and that as I went forward in life as a father, I needed to answer them. I wanted to be emotionally strong for the family I was starting and for that I needed to exorcise the remaining unresolved grief that lingered from Nick. In previous years I had occasionally considered a church service in his memory but it had not felt right and I had not found any other solution.

As the weeks following Amber’s birth went by, I realised that above all I was thankful for the gift of her life. That made me all the more aware that my own life was a gift. I had once come within a hair’s breadth of losing it. I owed my life to the couple who had pulled me from the water. Sitting by Amber’s cot, I decided to write them a letter. I walked to my study desk and took out a sheet of paper.

Dear Mr and Mrs Wood-Martin,

How easy it is in the hurly burly of life to hurry past the important things and leave them undone. In the more than 20 years of life I have had since you saved me from drowning after the bomb, it amazes me that I have failed to reach out and singularly thank you for doing for me the greatest service it is possible for one person to render another: to save his life.

Of course I remember talking to you at the wedding of Norton and Penny, and signing my parents’ Christmas cards many times since, but these are incidental. Only in recent years have I reached that point in my underlying emotional recovery to be able to understand enough about life, and surviving the bomb, to know that small steps like this one are vital in the ongoing process of integrating the past into a fulfilled and happy present.

Many a time in the several years of therapy I did in the mid nineties did I find myself talking about you, and resolving to write this letter. But I never did.

I remember reading an interview with you, and being fascinated to learn things about the bomb only you could have known. It was helpful, as indeed is writing this letter. I think others in my family have different ways of coping with the grief. Of all of us, I think my mother and I share most closely the need to discover small and important truths, and to communicate with others about them. Occasionally, even publicly, because I’ve learnt how often it helps others.

One of my greatest frustrations is how rarely I am able to cry the deep cry I need to. Perhaps only a couple of times a year. And some people mistake the tears for pain, when of course they’re not, they’re the pain coming out. Writing this letter has been like pulling a big splinter of grief and emotion out of me, and the tears and relief have been enormous in so doing.

I recognise that no demonstration of gratitude could adequately repay the gift of continued life you gave me in 1979, nor express sufficiently what I feel. So all I will say is thank you. And ask you to bear in mind every day that somewhere else in the world is someone loving the miracle of life thanks to you.

And what a miracle it is; my wife Isabella gave birth to our first child, Amber, on January 3rd, and never have I known a baby smile so much, reflecting back perhaps our own happiness.

When and if our paths will cross I do not know; either by design, or chance as they did once before. But somehow I feel they will. Until then my love and every good wish,

Timothy

Two things surprised me. First, it was a very quick letter to write; it flowed almost as if by reflex. Second, writing it made me cry. I had difficulty in keeping the writing paper dry, just managing to keep it away from my waterfall. I was determined not to make the letter look ridiculous by smudging it with tears. I stifled the noise of my crying because I did not want to upset Isabella, or interrupt either the letter or my tears, both of which were very therapeutic. I sat back thinking that if this letter to people I hardly knew had produced such a powerful reaction, then I must go back to Ireland and explore everything that had lain dormant in my psyche for so long.

‘IRA’

When wanting to bring order to Burma after the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, my grandfather, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, insisted that the Burmese nationalist leader Aung San, aged thirty, was to lead the government. The British civilian governor remonstrated and my grandfather fought him, even having him temporarily sent back to London. As Viceroy of India in 1947 he took a similar line, insisting that power be handed to the very nationalists who had previously been locked up by the British. He was being more than practical; he was following his own instincts and ethics.

One day in 1975 he went for a drive in the area around Benbulben, the mountain that dominates the Sligo skyline. He took pleasure in discovering for himself a piece of IRA history from earlier in the century. A monument nearby was inscribed: ‘On this spot Captain Harry Benson and Volunteer Thomas Langan gave their lives for the republic, 20 September 1922.’ He discovered that they had been killed during the Civil War by forces of the Free State and that a wooden cross had been erected on the mountain that year which had been replaced by a granite one in 1947. He photographed it and put the print in his photograph album with the caption: ‘Grave of 2 IRA officers killed on the estate in 1922 on Ben Whiskin, opposite Ben Bulbin’.

Finding this photograph in 2003, I was struck by three points. First, that he should take the trouble to find the spot on the top of a mountain, miles from the main road. Second, that he should want to put a photograph of it in his album. Third, that he should use the same term for these men as for those on earlier pages of his album who had died under his command in the Second World War: ‘officers’.

He plainly loved and respected Ireland’s political and cultural heritage and had not been put off returning to Classiebawn even when the Cabinet Office in London had pointed out: ‘If you had no IRA man on your estate you would probably be the only landowner in the Republic of whom this could be said!’

‘Face to Face’

Dr Harbison was answering my questions with care, expertise, patience and honesty but I knew that one last step remained: the photographs. I was tense, preparing to look at the photographs of my beloved 14-year-old identical twin. I would of course have declined had it not been for the aching pain I had felt for 24 years at never having had a last look at Nicky. I had never seen him dying or dead. And by the time I reached his grave 7 days after his funeral my child’s mind had hung in blank incomprehension. I had wondered if he really was in that grave at all. I had wondered what his remains looked like. Those questions had been in my head for 24 years. Now I had the chance to come face to face one last time.

For some seconds I looked at the first photo. I could feel myself digesting the information coming off the photograph. It was a process that absorbed me. Then I lowered my eyes to Nicky’s chest and quite unexpectedly the steely calm left me and a stirring feeling welled up from somewhere low in my chest. For a second or two my eyes got blurry with tears. I blinked and my mind took over again, my stirring feeling left, and I was able to say very quietly, ‘That’s the jumper Nanny knitted.’ I hadn’t thought of that jumper since I last saw Nicky. It had completely gone from my mind. Now I looked at the photograph, the thing that knocked me sideways was not the state of his body; I had prepared myself for that. It was the knitting of Nanny in whose woollen V-neck he had been killed. She had been like a second mother. For the last couple of years she had stopped coming to Classiebawn with us, staying instead at home in Mersham. In 1979 she was 87 and she wrote on hearing that Nicky was dead that her heart had broken. In Professor Harbison’s office I just had not expected to have Nanny there with me, but I looked at that lovingly knitted little V-neck, whose individual strands of wool were so clearly caught by the Garda photographer’s camera, and it wasn’t Nicky’s body that jolted me, for it was utterly lifeless and painless; what jolted me was the sudden reminder of the living pain that Nanny went through for the last years of her long life. She died five years later.

‘Peace’

In 1979 I came away from Ireland with an understanding of the country and its people which was that of an innocent fourteen-year-old. I did not ask difficult questions and this helped me get along happily, largely untouched by suspicion, fear and hate. My return to Ireland equipped me with a far greater understanding of the situation in which I had been immersed and an equally greater understanding of my own feelings. I gained a firm basis for the forgiveness which had crept over me in the intervening years. Perhaps the most difficult question was how I felt about Thomas McMahon. At the end of the year I accepted at least this: that if I had been born into a republican stronghold, lived my life as dictated by conditions in Northern Ireland, and been educated through the events of the 1960s and 1970s, my life might well have turned out the way Thomas McMahon’s did. In this respect I felt ultimately inalienable even from him.