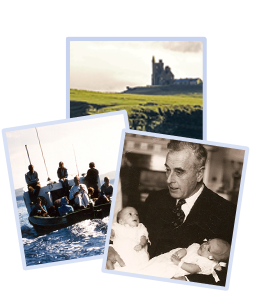

On the morning of Monday 27 August 1979, Paul Maxwell asked me the time. He laughed when I told him it was eleven thirty-nine and forty seconds. We were as carefree as skylarks, out together in my grandfather’s small fishing boat off County Sligo on the west coast of Ireland. My identical twin brother Nicholas Knatchbull was a few feet away, tinkering with something in the cabin. We were fourteen, Paul was fifteen.

The sun was warm, and the sea flat and calm. We were enjoying ourselves like countless other families that morning. My grandfather was at the helm, looking very content. He was never happier than when mucking about in a boat. In this respect he was unremarkable; what was less normal was his life story. At his christening, Queen Victoria had been his godmother. He had joined the Royal Navy as a small boy and had retired having been the head of all British armed forces, a Supreme Allied Commander in the Second World War, and the last Viceroy of India. Now in old age he was still internationally famous. His name was Earl Mountbatten of Burma; to us he was Grandpapa.

A few paces away in the stern sat his daughter, my mother, her feet up in front of her. In her lap she had her little dachshund, Twiga. Not far from her in the middle of the boat was my father and to her left his mother, who now said, ‘Isn’t this a beautiful day?’

A few minutes later Paul, Nick and my grandfather lay dead in the water. A bomb had detonated under their feet. The wooden boat had disintegrated into matchwood which now littered the surface, and a few big chunks which went straight to the seabed. My grandmother was pulled into a nearby boat but died the next morning in the Intensive Care Unit of Sligo Hospital. She was eighty-three. I lay in the bed beside hers with wounds from head to toe. Surgical tubes led into my body. Opposite, my mother was connected to a machine that breathed for her; she was not expected to live. Her face was unrecognisable, held together by one hundred and seventeen stitches, twenty in each eye. In a nearby ward lay my father, his legs twisted and broken and multiple wounds all over his body. Between the three survivors, we had three functioning eyes and no working eardrums. The bodies of Paul, Nick and my grandfather were pulled out of the sea that day. Twiga’s corpse was recovered the day after.

The bomb had been hidden on the boat early that morning by two members of the Irish Republican Army. By killing my grandfather they hoped to draw attention to the long struggle for an end to British rule in Northern Ireland. They got plenty of attention.

The world mourned. Every newspaper headlined the news of his assassination. Letters in their tens of thousands poured in upon the survivors. In Rangoon, Burma a book was opened in the Embassy for people to sign in tribute; for four days people queued before it, the line often stretching far out into the garden. In New Delhi, every shop and office was closed, a week’s state mourning was declared. The rulers of the great nations hastened to express their sympathy.

Paul was buried in Enniskillen in Northern Ireland; my grandfather’s funeral was held in London; Nick shared one with our grandmother in Kent. Meanwhile, my parents and I lay helplessly in our hospital beds in Ireland. The kind nurses put my parents’ beds together and wheeled mine opposite theirs. At night they held hands. It was the first time I saw my father cry.

When our injuries permitted, we returned to our home in England and a mass of supportive letters. Many of the writers were unknown to us. We replied to those who gave addresses.

Stephen Street, Sligo.

January 22nd 1980.Dear Timothy

This is just a short note to let you know that we all in Sligo appreciate that your loss in the tragedy in Sligo was very special.

I hope that your injuries are now healing well and that time is taking the sharpness from the pain of the great loss of your brother.

There is now a great responsibility on you to help your parents through this terrible year and also since you have been close to the tragedy to be an example to the civilized community and to the oncoming generations.

Soon in the future when all this trouble will be over I hope you can enjoy this lovely part of the world which God put here for us all to enjoy.

Again Timothy my deepest sympathy and try and understand and forgive Ireland for your terrible loss.

Yours very sincerely,

Dr Desmond MoranCoroner for Sligo Borough & North County Sligo

Having read the letter I withdrew into a room at the back of my parents’ London home. I wanted to read it again without interruption and think. It was the first time someone had expressed what was already in me: the wish to return to Ireland.

On the day we had left Ireland I told my family that I was going to return. They told me that would never happen. I repeated myself but they were firm. In the circumstances they were right. The security services had already visited my father in hospital and told him that we would always remain possible targets as survivors of an attack that had received so much publicity.

Twenty-four years later, I did what I had always wanted. I spent a year travelling back and forth to Ireland, staying for up to ten days at a time. I wanted to discover what had happened, and understand it; and forgive. I wanted to meet old friends and say the goodbyes I had missed. I wanted to stop hearing the sound of the bomb as I went around my daily business. I got everything I went for and much more. This book is that story.