Timothy Knatchbull

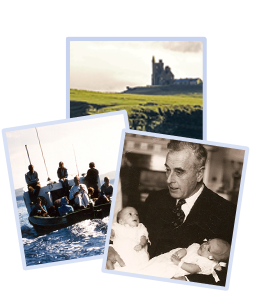

Well it was an absolutely beautiful day; gin clear, no wind, a mild, flat calm sea. You couldn’t want a more beautiful morning to go out on a family boat trip which is what we did.

My grandfather who was then seventy nine and my grandmother who was eighty three – that’s my maternal grandfather and my paternal grandmother, so different sides of the family – my twin brother Nicholas Knatchbull. He was an identical twin, twenty minutes older than me; we’d led fourteen years pretty inseparable life. We’d only had a few days in our lives where we had been separated. So on the boat were my parents and there was also a wonderful local teenager, Paul Maxwell, who had as a summer job, helped look after this small, delightful little wooden, twenty nine foot fishing boat which my grandfather had built nineteen years previously.

We set out to do some fishing and to lift some lobster pots. We had only gone a short distance maybe half a mile or a little over when there was an extraordinary explosion. My memories of that are really just of a sensation and then being lifted into…Well I don’t remember being lifted. I remember coming round in the bottom of a small boat with a wooden floorboard I was lying on and hearing some very emotionally charged, Irish voices and knowing that something was dreadfully wrong. Although interestingly at first I could not work out what was wrong with me. I didn’t have any sight; I couldn’t tell where pain was coming from, if indeed there was pain.

I was really aware of one over-powering sensation which was an intense cold that had really got a grip in me and which I’ve never really known the like of since. I knew that if everything was to be alright, I had to concentrate very, very hard and if I possibly could, communicate to those around me what was wrong with me. I was frustrated I couldn’t work out what was wrong with me.

Roger Hearing

Because you were quite badly injured, weren’t you?

Timothy Knatchbull

I’m told when they got me to hospital they weren’t sure if I was going to live. They put me into Intensive Care in a bed opposite my mother and beside my grandmother. My grandmother died about twenty hours later and my mother was given a 50/50 chance of living. She had an unrecognisable appearance: 120 stitches in her face with 20 in each eyeball.

I wasn’t as badly wounded as her but nonetheless they were not sure if would live or die. They gave me an emergency operation and my first memories in hospital were coming out of that operation and coming round in Intensive Care.

Then only three days later being told the news that changed my life, which is that my identical twin brother, Nicholas, was dead.

Roger Hearing

Along with other members of your family of course. It’s something that hopefully none of us will have to experience. The shock must have been profound?

Timothy Knatchbull

It was. I was incredibly lucky both with the level of care from the holiday makers and the local residents in the village who had pulled us very, very quickly out of the water. And then we were rushed to hospital, a brilliant hospital with brilliant doctors, one particularly brilliant doctor who led a team there.

We returned to England about two and a half weeks later. My parents continued their recuperation in hospital but I was able to lead a family normal life from thereon. I had no loss of limbs but although I had lost the sight in one eye and some of my hearing, I had no ongoing injuries except that I found later that there was a certain degree of emotional and mental overhang that really came from the fact that I had been unable as a fourteen year old to go back and to address the emotional wounds. Particularly I never had the chance to say goodbye to my dead twin. That was something that really had a terrible grip on me in later years.

Roger Hearing

How did that manifest itself?

Timothy Knatchbull

Well amongst other things I carried around some emotional and mental scars. One was that very often I would imagine that I heard the sound of the bomb, time and time again. Sometimes half a dozen times in a day. Often triggered by some sort of electrical impulse: the ringing of a phone, the turning on of a light switch, as if what was being brought back in my mind subconsciously was a connection between the electrical wiring or a radio signal. It was believed the bomb was triggered by a remote control signal.

Roger Hearing

So a kind of echo of what happened?

Timothy Knatchbull

Indeed and I decided after many years, in 2003 and by then I was happily married with children, I had a level of emotional security in my life where I felt strong enough to go back and do what I’d always wanted to do, which is to go back into the West of Ireland. I went and spent a week there in August 2003 to coincide with the 24th anniversary of the attack. And then each month after that, very quietly, I slipped back and spent a week in the West of Ireland in order to make contact again, to ask questions, to talk, to reflect with the people that we had known in my childhood – our neighbours, our friends, our relatives in the West of Ireland. And to learn from them, share with them my thoughts, my aspirations, hopes and questions. Because really I found when I looked into it that I was not as able as I wished to enter into a really deeply forgiving mindset for what had happened.

Roger Hearing

Of course some of the people who are sympathising with that are now, if you like, the establishment in Northern Ireland. Some who expressed at the time even, a measure of acceptance of the people who had done that and why they had done it. That must be hard?

Timothy Knatchbull

No it isn’t hard. I think we all have a responsibility to remember what small creatures on this earth we are. There are bigger forces at work and it’s for the sake of oncoming generations we need to embrace, salute and applaud those who have been part of this process. Whether or not they have been implicated in the murders of yesteryear we have to dig deep and remind ourselves of the need and the healthy impulse of always looking to the future and being prepared to lay the rest to past, to let old wounds heal and above all not to open up fresh ones.

Roger Hearing

Can you understand the motivation and the level of the people who put that bomb on the boat?

Timothy Knatchbull

I’ve written in my book that at some deep level, I accept that had I lived through the events of the 1970s, had my life been informed by circumstances through which they had to live, circumstances they had to endure, I can’t say for certain that my life would have ended up in a different path from theirs. And at that level even those who were involved or supported this attack, even from them I feel ultimately inalienable. I understand a great deal more now about the need for forgiveness on both sides of the equation.

Roger Hearing

Do you forgive the people who destroyed part of your family and injured you?

Timothy Knatchbull

I’m benefitting hugely from this process of reaching a greater state of mental and emotional forgiveness which is a life long journey and I’m pleased to be in it.

Roger Hearing

But you’re not there yet?

Timothy Knatchbull

Well I certainly feel that the events of going back to Ireland 2003 and 2004 were enough to push me across that divide. So I can say, yes, I’m much healed and much more forgiving. I’m hesitant to come up with these neat clipped expressions, like ‘I have forgiven’ because I think forgiveness is a much more complicated process. It’s a chronological process, it’s an ongoing process. You have to be a bit like being healthy in your body, or your mind, or your soul. It’s about working at it continually and reminding yourself of the need for forgiveness. But if you want to push me in one direction or the other, yes, I would say, forgiveness is where I am at now.