Michael Buerk

Our next witness is Timothy Knatchbull who lost his grandfather, Lord Mountbatten and his twin brother 30 years ago in an IRA bombing in Ireland and has recently written about it in a book called From a Clear Blue Sky. You have got yourself to a state of forgiveness, how long did it take you and why was it so important to you?

Timothy Knatchbull

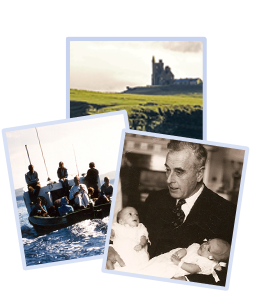

In 1979 I was a boy of fourteen and I left Ireland with a terrific numbness and traumatic failure to really comprehend and to connect, particularly to say goodbye to my dead twin, my identical twin brother, Nicholas. I went back to England and got on with life and then many years later as a father, very happily married to my wife, Isabella, I started to address the fact that I knew something was wrong inside. I was having some mental and emotional symptoms. I felt secure enough to go back to Ireland. While I was there I tried to unpick the story that had happened and understand it. I spent about a week at a time there each month for about 12 months, this is in 2003, 2004. I felt that one of the things I came away with was this sense that I’d really left in a state of ignorance. A veil of ignorance had descended upon me about really what had happened; who had attacked us, how and why. Somewhere, I felt that my forgiveness, although it was there, it was lacking, it was a complete process.

Michael Buerk

It was a quest for understanding in a sense?

Timothy Knatchbull

Exactly.

Michael Portillo

You and your family have had this terrible experience and you have dealt with it in an absolutely remarkable way. And as Mr Bowman (previous contributor) has just said, he would accept that each person would approach this differently. But I wonder whether what you have done for yourself wouldn’t go too far for all of society. In the sense that I believe you’ve reached a very high level of understanding. You think there was a war going on between the IRA and the British Government; you think your family were symbols of the British Establishment. Am I right in thinking that is what your position is now?

Timothy Knatchbull

Broadly speaking, yes it is. I take the thrust of your question which is: is it going too far and could it work on a wider scale. Well, I just have to answer that as an individual. With my limited experience and knowledge and the horizon that I can see, and an awareness that just occasionally I would come across or I would overhear people, who were saying, ‘we can’t allow for this peace process in Ireland to go further. There are men and women with blood on their hands; we can’t have them in power. We have to think of families of the people who have been killed, maimed and made miserable. It would take my breath away’. Well I would say, ‘don’t stop the peace process on my behalf, on the contrary. We need more of that’. And I hope that goes someway to answering your question.

Michael Portillo

It does and I entirely understand what you are saying but I’m not sure that moving forward politically or even moving forward socially, needs to rest upon forgiveness and I certainly don’t think it needs to rest on changing your view of the past. I’m a former politician I don’t accept that there was a war. I think there was a series of terrorist outrages within a democratic society. I don’t accept your grandfather, who was a war hero and a member of the royal family, was a legitimate target. I don’t accept any of that. But I’m not against the peace process.

Timothy Knatchbull

Broadly I am in agreement with you on those points. But really underlining this is that I didn’t go back to Ireland to engage in a political process, I went back really to engage in a human process to try and heal myself, say goodbye and expunge a lot of the negative and awful stuff which I needed to say goodbye too.

Melanie Phillips

I want to explore this business of understanding which seems to be crucial to your process of healing. You went back to Ireland, you understood, you forgave, you healed. Am I right in thinking therefore that the process of understanding in your mind made the atrocity less awful?

Timothy Knatchbull

No, it didn’t make it any the less awful; in fact in some ways it threw it into sharper relief and made it all the more breathtaking and disgusting. But you used the word I’d like to pick up on. You said ‘a process of understanding’ and I take that further and I say it’s a process also of forgiveness. I don’t quite understand what people mean when they say, ‘have you forgiven?’ or ‘I’m glad you’ve forgiven’, as if forgiveness is a moment and having had that moment – a sort of Eureka moment – that you’re suddenly in calm water and winds on your back. I think that forgiveness is a process and it’s a bit like being healthy or being fit or not being overweight. It’s something you get up and work at every day. The point that you make about gaining understanding is the core of this: understanding and acceptance and trying in some small way to walk in the shoes of others.

Melanie Phillips

Well that’s a very interesting point. Can I ask you therefore if you think that you might be able, or that one might be able to apply that to other circumstances? You came to understand what was basically a political situation but do you think that one could understand the burglar, the mugger, the rapist? In that one could understand that these people have come from circumstances which have led in a process to the crimes they have committed. What I’m getting at is this: that when you used the word understanding, are you actually using is at a synonym for a kind of sympathy? Not for the act but for the cause?

Timothy Knatchbull

I think it’s more complicated which is a frustrating answer I’m sure, because the joy of a programme like this is trying to get things into neat, clipped answers. The reality of this is that it is more messy than that. I don’t have a simple clipped answer but I think that, I came away with a sense that by understanding more I could ultimately address this issue. Which is: could I definitely say that if I had been in the circumstances in which the people who had attacked us, had grown up, conditions they had suffered, the horizon that they had existed within, could I say for certain that the human capital that was in me – my soul – was definitely not going to turn to the path which they turned to. And I found ultimately I couldn’t answer that for certain. That shocked me. But it also allowed me to go a bit further forward on my journey.

Michael Buerk

What is the kind of texture, the nature of your forgiveness? Is it intellectual forgiveness, an emotional forgiveness, a religious forgiveness?

Timothy Knatchbull

I think it’s a little bit of all of those at its most basic level. It’s just a human process of me trying to and succeeding happily to gain to a point in my life where I could accept and understand and move forward and enjoy this incredible gift of life now. And move forward and welcome all the possibilities that life has instead of getting cornered into all the avenues that were shut off for my dearly beloved twin brother, Nicholas.

Michael Buerk

Timothy Knatchbull, thank you very much indeed.